Narrating dance

Isabel Raabe

Curator and cultural producer Isabel Raabe wonders whether dance as a body-based and ephemeral art form can be archived at all and proposes a strong emphasis on its social, spiritual and political dimensions in order to counter the ‘impossibility’ of a dance archive. She reports on the dance section of the pioneering project RomArchive -Digital Archive of the Roma, which she co-initiated. The digital archive makes the artistic and cultural work of the Sinti and Roma visible and is an exemplary model for an archival practice that seeks to resist labelling, discrimination and stereotyping.

On the archival practices of the "RomArchive - Digital Archive of the Roma ”

The digital archiving of ephemeral art forms, especially dance, is a major challenge. I would like to ask the question whether dance can be archived at all and whether an inclusion of the social, spiritual and political aspects of dance can help to overcome the difficulties of archiving. In doing so, I will take as an example the dance section of the “RomArchive -Digital Archive of the Roma“.

Dance takes place in a variety of contexts and is practised for different reasons, be they social, ritual, religious, therapeutic, educational, theatrical or political. Societies and cultures from all over the world have used dance, movement and the body to survive, communicate, interact, grow and evolve. Dance is an art form with an intangible character; therefore, it is all the more important to document and archive it. But how can this ephemeral art form that finds its expression in the body be archived? Can the moment of interaction of the dancers in space, time and with spectators be documented at all?

The power of the archive

Let us first turn to critiques of the archive. The French philosopher Michel Foucault emphasized the power structures that are connected to the archive. (annotation 1) He argued that archives not only store information but also exercise control over knowledge and memory. In the context of dance, this means that the selection and conservation of dance works in archives has a political dimension. Digital archives at least make it possible to a certain extent to decentralize these power structures by making access to dance works more widely available. But the question remains: Who brings the collections together? Who catalogues and sorts them? Who is excluded from the archive?

Similarly, the French philosopher Jacques Derrida considered the archive as a place of hierarchy and of the suppression of voices and histories. He called for a dismantling of the archive to allow for alternative narratives and perspectives. Applied to a dance archive, this means it must present different interpretations and perspectives on dance works and practices in order to do justice to the diversity of the art form.

And what brings dance to the archive?

As with any form of preservation, the preserved object changes. It is comparable to the process of fermenting. Through fermentation, a food is preserved, and at the same time its flavor, its consistency, its smell changes. Dance, in particular, changes. Can it even still be called dance? American scholar and feminist Peggy Phelan, founder of Performance Studies International, emphasizes that performance lives only in the present. On the “ontology of performance” she writes the following:

„Performance cannot be saved […] Performance’s being […] becomes itself through disappearance“ (annotation 2)

Performance cannot be saved or documented. Attempts at this become something other than performance. The literary and media scholar Philip Auslander takes it a step further and speaks of a performativity that emanates from the archived performance document itself:

„It may well be that our sense of the presence, power, and authenticity of these pieces derives not from treating the document as an indexical access point to a past event but from perceiving the document itself as a performance that directly reflects an artist’s aesthetic project or sensibility and for which we are the present audience.” (annotation 3)

Upon these reflections on archiving dance, I’d like to point out both the limitations and the possibilities of a dance archive. What we find in a dance archive is never the performance itself. What we find are notations, photographs and videos, interviews and press reports, program flyers and postcards. But is it perhaps precisely the information that points to the social, political and spiritual significance of dance that is most exciting? This was the approach taken by the curators Isaac Blake, Rosamaria E. Kosnic Cisnero, Daniel Baker and Adrian Marsh of the dance section of the RomArchive – Digital Archive of the Sinti and Roma.

The archival practice of the RomArchive - Digital Archive of the Roma

The RomArchive presents the arts, cultures and stories of the Sinti and Romain Europe and beyond in ten curated sections. The digital archive was funded by the German Federal Cultural Foundation (Kulturstiftung des Bundes) and went online in 2019. I was the co-initiator of this pioneering project, of which the content was the responsibility of curators from various European Romani and Sinti communities. In total, over 150 people from over 15 countries were involved in the implementation of the digital archive and the compilation of over 5000 specimens.The central concerns of the RomArchive are Romani leadership and recognizing and making visible the artistic and cultural work of Sinti and Roma. It seeks to resist the labelling, discrimination and stereotyping of Sinti and Roma, who with twelve million people are the largest “minority” in Europe. The project won the European Cultural Heritage Award 2019 and the Grimme Online Award 2020.

In the set-up phase we spent a long time developing ethical guidelines and an associated collection policy for the compilation and presentation of the collections. The ethical guidelines define the objectives of the archive and set the framework and principles for the whole project. The collection policy clarifies how these guidelines affect the compilation and presentation of the collection. For example, as the overarching principle these guidelines advocate for self-representation and Romani leadership, i.e. decision-making and interpretative sovereignty in the hands of Sinti and Roma. They also regulate how stereotypes or other hurtful representations of Sinti and Roma are dealt with in the archive: through deconstruction and contextualization in order to avoid re-traumatization.

In addition, we looked intensively at archival ethics and technology, which cannot be separated from content creation. If we look at a search engine and the thesaurus it relies on, we notice that technological concepts are never neutral. Archived knowledge is hierarchized by the structure of databases and keywords determine the results of search engines. Cataloguing and key wording must therefore be implemented with great care and sensitivity. The curatorial concepts of the different archive sections were very different. The curatorial team of the dance section chose an interdisciplinary approach reflecting the interdisciplinarity within the four-member curatorial team: Isaac Blake is a dancer and choreographer, Rosamaria E. Kostic Cisneros is a dance historian and flamenco dancer, Daniel Baker is a visual artist and theorist, Adrian Marsh is a historian. The curators’ vision for the dance section of the RomArchive is to showcase the diverse traditions, innovations and global influences of Romani and Sinti dance and to present the dance heritage and cultural identities of different communities.

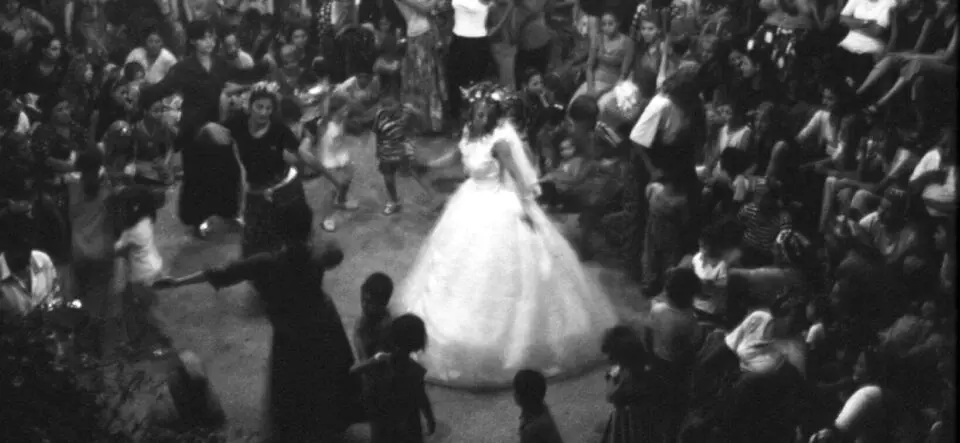

Sinti and Roma live all over Europe. Their cultural traditions developed separately and are usually interwoven with national cultural practices. This is also the case in dance. The curators therefore decided to work with existing collections (mostly private collections) for their dance archive and to divide them according to geographical regions: the Judith Cohen collection (Bulgaria and Portugal); the private collection of curators Cisneros und Baker (Spain); two separate mini-collections of Péti Iourtchenko und Simon Renou (Russia and France), linked through a teacher and student relationship; a collection of photographs and drawings from the Hungarian Academy of Sciences; the Ivana Nikolic collection (Italy and Serbia); the Blake und Cisneros Privat Collection (UK); the Clog Dancing Collection (UK); the Private Collection Adrian Marsh (Turkey); the collection of the renowned Romafest Dance Ensemble (Transylvania/Central Romania); a collection on the most important Roma dance festivals (France and Norway); and the India Collection from Rajasthan, considered the region from which the Roma once left for Europe. In addition, theRomArchive has dedicated a separate section to flamenco, which became apart of Spanish national culture without sufficient acknowledgment of its origins in Romani culture.

The collections of the dance section mainly contain photos, posters and program notes, objects (costumes, tambourines, figures) and some videos. Following the practice of “digital storytelling”, these are integrated into contextualizing texts. The curators pursue different critical approaches in the presentation of the collections. The sociological approach focuses on the social interconnections, while the ideological approach examines the patterns of meaning and ideas encoded in the content. The structuralist approach analyses the meaning of collection objects in relation to dominant power structures. The gender-specific approach focuses on the representation and construction of gender roles. All approaches are interrelated and can complement each other. It is not dance itself that has been archived here, rather, to return to Peggy Phelan’s thesis quoted at the beginning: dance is narrated here.

Annotations

- Michel Foucault “The Archeology of Knowledge”. 2002. Routledge, London.

- Peggy Phelan “Onthology of Performance”in “Unmarked. The Politics of Performance. 1993. Routledge. p. 143.

- Philip Auslander “The Performativity of Performance Documentation” in PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art (28). 2006. Cambridge, Massachusetts.